Participatory Assessments Focusing on Intended Target Groups: A methodology to leave no one behind

Participatory assessment (PA) aspires to assess an intervention and its results from the perspective of its ‘beneficiaries’ or primary stakeholders. As an alternative to external reviews, the PA approach puts the people targeted by an intervention at the centre, focusing on their active and meaningful contribution to the analysis – and ultimately to the intervention.

Introduction and Background

From beneficiary assessment to participatory assessment: leave no one behind!

Participatory assessment can be applied at different stages of the project cycle management. If designed accordingly, the participatory assessment methodology helps translate the motto ‹leave no one behind› into operational work. The PA helps primary stakeholders – e.g. communities, groups and individuals left behind – to overcome obstacles in making their voices heard. It is a tool for integrating excluded people’s views into planning and designing more effective, inclusive and sustainable interventions. The PA has great learning potential for stakeholders as well as project management.

Participatory assessment was formerly called beneficiary assessment (BA) and is used in a variety of forms by donors and NGOs, including the SDC. ‹Beneficiaries› is a somewhat out-dated term alluding to a rather paternalistic view of development assistance. This is not in line with the current rights-based thinking on development, focusing on empowerment and active participation. We thus prefer the new term ‹participatory assessment› as it reflects the active role that target groups are expected to play in assessment. How do they perceive the intervention at stake, its results, approaches and methodologies? How useful are the results in their real life? What support would they really need to overcome obstacles, achieve results, not be left behind? How could our interventions improve?

See how beneficiary assessments contributed effectively to SDC's work

Practical cases from the SDC’s experience show that the participatory assessment methodology works and provides interesting inside viewpoints. Compared to other assessment methodologies, useful results depend even more on the careful scoping and definition of objectives from the beginning, continuous reflection on the process design, and clarity about the roles of different actors, taking into account the context at stake. It is particularly demanding in terms of resources, and the cost-benefit ratio has not always been satisfactory, often due to limited investment in the initial phase and the setting-up of the process.

There is no ‹one size fits all›. At the same time, we do not need perfection in every step. We can approach the PA pragmatically, although with due reflection on the key elements of the methodology.

Southern Africa — © Flaticon by Kalashnyk The BA Process: Bulisani Ncube, SDC Regional Programme Manager, Southern Africa

Southern Africa — © Flaticon by Kalashnyk BA Results Informing Future Action: Bulisani Ncube, SDC Regional Programme Manager, Southern Africa

Ethiopia — © Flaticon by Kalashnyk Ethiopia 2013: Beneficiary Assessment of the ‹Rehabilitation and Improvement Water Resources in Borana› Project

Latin America — © Flaticon by Kalashnyk Latin America: BA contributes to increased relevance, strengthened relationships & empowerment

In Latin America, where political contexts encourage a high level of civil society participation, BAs appear to have enhanced the relevance of development programmes. By seeking farmers’ perspectives on the technical, economic, social and ecological soundness of an agricultural programme (PASOLAC) BA was able to identify the 5–8 preferred and most effective soil conservation techniques. It also allowed farmers to challenge the government extension services and make them more responsive. The farmers actively challenged assumptions that such approaches are sufficient, arguing they need access to more formal research-driven agricultural innovation that addresses real farmers’ needs.

The PASOLAC BA also had unintended outcomes likely to enhance the impact of the programme.

1) Farmer assessors’ questions about soil conservation techniques provided a relatively cheap and simple approach to estimating the adoption rate of different techniques, which are usually estimated with more expensive survey instruments. At their own initiative, they also broadly shared agricultural knowledge and innovations, including some research findings, with communities they visited. This allowed sharing of useful knowledge, with the potential to enhance impact.

2) Having been empowered by their roles as citizen observers, farmers surprised project staff by asking staff to organise workshops where they could present proposals for the next phase of the programme. The SDC was transparent in explaining that although these individual inputs were important for influencing the programme, it could not respond to proposals on an individual basis. 3) As a result of the BA, relationships and trust between farmers and partners were strengthened.

Madagascar — © Flaticon by Kalashnyk Madagascar BA: increased responsiveness and empowerment

The Madagascar BA findings influenced planning for the next programme phase and decisions to institutionalise more participatory M&E approaches. It also influenced changes in the language programme staff used when talking about ‹beneficiary› assessors. At the beginning they were referred to as ‹the peasants›, who staff viewed as lacking the capacity to undertake research. By the end of the BA, when the assessors had presented findings to government officials, the staff described them as ‹citizen observers› (COs).

Moreover, whereas at the beginning of the BA citizen observers relied on the local facilitator to translate for the general facilitators, once they gained confidence, those who spoke rudimentary French began intervening, telling the local facilitator, ‹you didn’t translate properly!› One general facilitator commented on this indication of empowerment: «I think what we witnessed was the COs gradually realising that they too could argue and confront the facilitator’s interpretations and take matters into their own hands.»

Laos — © Flaticon by Kalashnyk Laos BA: a turning point for the SDC

A BA in Laos proved an important learning and turning point for SDC. It enabled SDC staff to get beyond the perspectives of partner intermediaries, in this case the Laos National Extension Service, which was focused on technical approaches to enhancing agricultural productivity that tend to benefit the wealthy. By engaging poor farmers in a BA it was possible to discern the effects of extension work and identify weaknesses in the impact hypothesis. People from different wealth groups valued extension services for chicken, pigs and rice differently.

The findings that revealed that programme effects are mediated by power relations. This lesson has since become central in the SDC's policy discussions with the partner. The BA findings helped enable the steering committee to advocate a pro-poor agenda in dialogue with the national extension service, and raised awareness of the benefits of extension service providers listening to poor farmers' voices. They have successfully advocated for a broader range of proposed services and differentiated service provision: 1) for farmers with access to market, and 2) for poorer subsistence farmers without access.In November 2022, this new guide on this page was launched by SDC together with the experts Jo Howard (IDS) and Erika Schläppi (Ximpulse) in a webinar. If you have missed the webinar, you can access the slides here below. In addition, you may read the input by Jo Howard on the importance of participatory methods for Leaving No One Behind

and find questions put forward during the webinar answered here:Participatory Assessment: A Methodology to Leave No One Behind | Questions and Answers from webinar

PDF177.88 kB23 November 2022

Participatory Assessment: A Methodology to Leave No One Behind | Launch webinar slides

PDF2.67 MB23 November 2022

Participatory Assessment: A Methodology to Leave No One Behind | Accompanying text to IDS/Jo Howard's inputs

PDF147.96 kB23 November 2022

Why Focus on the Active Involvement of Target Groups?

Various reasons speak for integrating target groups in an active role in assessing intervention contexts and results – making their views more relevant for the design and implementation of programmes and projects.

1) Participatory assessment helps implement the SDC’s principles

Firstly, involving the people targeted by the intervention means taking the SDC’s missions and values seriously.

Alleviating poverty and contributing to sustainable development in accordance with the 2030 Agenda are at the core of the SDC’s international cooperation mandate. The SDC is committed to leaving no one behind, and the benefits of the poor and other vulner

able and marginalised groups are key indicators of the success of development cooperation and humanitarian aid.Another key SDC approach is empowerment and participation – enabling target groups to make their voices heard and take their lives in their own hands.

Instead of talking about people and discussing among experts and managers about the effects that our programmes may have on them, the PA aspires to talk and listen to them.While the PA can help strengthen the ownership of target groups in the intervention at stake, its empowering effects may have a wider impact on the context and social relations, building social capital beyond the intervention at stake.

Finally, the PA is also about accepting and respecting diversity. Targeted groups are never homogenous – some may benefit from the intervention, others less or not at all. A variety of original voices can give a more complete picture and understanding about the reasons for this diversity – compared to our own views, the views of representatives or experts talking for and about them.

2) Participatory approaches help adopt a systemic and responsive approach

Secondly, involving targeted groups means working more systemically and effectively, by listening to authentic views, collecting primary data and relevant information, identifying and responding to real needs, addressing practical obstacles for and contributing to their empowerment.

When analysing the country or thematic context, when designing a programme or assessing the results, a systemic approach is important. Among other things, it means that the context, the programme design and its results should be looked at from various perspectives. While the views of a variety of stakeholders must be taken to account to get the full picture, the perspective of the targeted groups is particularly relevant.

Knowing their perspective helps us assess their needs and interests and taking into account their values adequately, in real time, and be responsive to their needs.

This is based on implicit key assumptions: those targeted have a better understanding of their own realities, what kind of intervention is useful to them and what prevents them from benefitting from an intervention. Target groups who are empowered to reflect on their needs and contribute to the intervention’s design are much more likely to reach agreed objectives than simple users or recipients who may not feel any ownership.

Their direct involvement will help improve the quality of our intervention, make it more responsive, accountable and produce more effective results.

3) Thinking out of the expert box

Thirdly, involving target groups helps us further develop – or confirm – our logic of intervention or theory of change (ToC). Do they share our views of how change happens, and how we can support change?

The reality that a programme is designed for can be perceived very differently. For example, the programme designers, funders, experts and managers might see great potential for a programme for introducing a new means of cultivation – while the farmers may have experience that speaks against it, or perceive major obstacles that external experts are not able to see.

Going beyond expert analysis and listening to the farmers gives a better picture of the realities of the context, adding real narratives to the causal logic of the logframe, ways of working and overcoming obstacles. This may challenge, confirm or help adapt the logic of intervention or theories of change.

4) Different meanings of the term ‹beneficiaries›

Interventions may target a variety of individuals, groups and institutions who are expected to benefit from the interventions in various ways. Directly or indirectly, they are all expected to benefit and their views can contribute to improving our understanding of the context and the assessment of results.

Some stakeholders use ‹beneficiaries› or ‹primary stakeholders› to mean ‹end users›, the people that ultimately benefit from the interventions, even if these are directly targeting institutions or groups.

Some use ‹beneficiaries› to refer to a broad target group (e.g. ‘the poor’), while others refer to more specific target groups or the group that the logframe addresses directly (e.g. the poor households in a certain village).

5) Usefulness of participatory approach throughout the programme/project cycle

Integrating the intended target groups’ views is a working principle and attitude which is useful at various levels and various operational stages throughout the project management cycle (context analysis, design and planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation). However, the PA methodology (as described on the following pages) is most commonly used to analyse intervention results.

A participatory approach, focusing on the views of target groups, can be used in various situations and processes at different stages of programme management for example:

… when assessing the relevant overall context of a country, or when analysing a problem: asking the views of a variety of stakeholders and potential target groups

… when designing and implementing a specific programme or project: reflecting on intervention logics together with intended target groups' views along the way, establishing spaces for joint learning (e.g. sounding boards, workshops, interviews, monitoring activities,…)

… when defining and conveying messages in policy dialogue with power holders: explicitly referring to and including the perspectives of specific groups and individuals.

… when analysing results of an intervention: did the intervention bring about change for the target groups? How to improve on results and outcomes?

… when thinking about remote management approaches: How can beneficiaries contribute to shaping the project/programme and evaluating its results?Beyond its traditional focus on programme management, a participatory approach can also be useful to help with conflict analysis and to develop the nexus between development programmes, humanitarian aid and peace building.

Main Aspects and Potential of the Participatory Assessment

Participatory assessment is particularly good at promoting learning and the discovery of new dimensions in a particular area or with regard to a specific intervention. Compared to other assessment methodologies, one feature of participatory assessment adds considerable value.

Target groups are not only asked for their opinions; target group representatives actively engage in the design of data collection, in generating insights and interpreting results. More concretely, the participatory assessment methodology aspires to deliver the ‹view from within› and to minimise external expert or management bias by collecting data directly from exchanges among target groups and their peers.

Biases are omnipresent.

Our perception of context and interpretation of facts is subjective. All of us have a conceptual and ideological framework through which we view the world around us. We explicitly or implicitly frame each situation in a certain way, which always leads to some kind of bias. Biases are omnipresent in our lives, but we are often not conscious of them or may experience blind spots. It is possible, but not always easy, to be aware of and transparent about our bias.

All assessment processes feature various forms of inherent bias, framed by the project set-up, the contexts, perception of local conflicts and the local political economy, the topic of the programme, the purpose of the assessment, the values, incentives and interests motivating the key actors in the assessment process, and perceptions of target groups and ‹peers›.

The participatory assessment methodology aspires to make biases more transparent and deal with them in a smart way, therefore leading to better results.

Participatory assessments do not exclude bias per se. Different types of bias play a role in the exchange between target groups and peers – and must be dealt with. Management and expert biases also persist in other phases of the assessment, for example in the framing of the process and the analysis of the collected data.

Biases, influence on perceptions and different forms of bias

What is a bias?

A bias is a tendency or inclination in our thinking processes in favour of or against an idea, a belief, a person or a group, closing our mind to alternative interpretations.

There are typical patterns of thinking processes and social dynamics that influence the formation of bias. Bias occurs unconsciously and automatically, although most people believe they are making a reflective and conscious judgement.

It explains why we so often make the wrong decisions, how we gloss over reality and why even experts often fail to deal with novel, unexpected dangers.

People also constantly overestimate their own knowledge and ability to reason. Experts are in fact especially prone to this – and particularly unwilling to admit this failure.

Biases occur, they are omnipresent, they are natural. On the other hand we gain a shared, enriched view if we reflect on them consciously.

Why do we have biases? The neurological dimension

External stimuli such as light or sound signals are recorded and transmitted to the brain. Our nerve cells communicate through simple electrical signals, however.

The nerve cells in the brain evaluate this information and then construct an image of the world with the help of previously stored patterns.

This means we remember the way things have always looked, and then reconstruct the norm.In creating images from the input we get, unconscious, automatic mechanisms come into play.

These mechanisms are influenced by biological factors (e.g. emotions, memories stimulating associative networks in the brain) and psychological factors (e.g. framing through language or specific words, the social environment).

What are the consequences of biases?

We refuse to take up information because it saves our brain's energy. Instead of trying to adapt and re-create new concepts to help us navigate, we stick to those that already exist. This mechanism is called cognitive dissonance.

Therefore, our perception diverges from the existing data. As a consequence, our decision making is based on a restricted data/information base, and our thought processes are based on distorted assumptions and riddled with logical errors.

What types of bias are particularly important in a PA?

We can distinguish between two categories of bias: cognitive bias, which is due to pitfalls in our perceptions of information and in our logical thought process, and social bias, which is influenced by our interactions with others.

A selection of cognitive biases

- Confirmation bias relies on automatic (fast) thinking, based on successful heuristics from the past which might not fit the current situation. Information and interpretation supporting our own pre-existing opinions are filtered, other information is ignored or underestimated. Often, contradicting information is not even sought, contradicting hypotheses are not formulated.

- Availability bias describes the tendency to use the information that is vivid in the memory (usually linked to emotions and unusual situations), or what seems to be ‹common sense›.

- Logical fallacies, such as confusing root cause and impact, or the tendency of our brain to invent a chain of reasoning (even if there is no causality) may influence the ways in which we perceive reality.

- Culturally learned underlying assumptions and mental models subconsciously frame and guide our interpretation of a message or situation.

- A gulf between declared intention and immediate action is observed in many decision-making processes. Even if all of the information is accessible, people may not behave ‹rationally›. Sometimes they choose what seems better at a specific moment, responding to short-term incentives and ignoring long-term, overarching goals. The benefits of the long-term decision are far in the future; the costs are a certain effort in the present. The further away the benefit seems to be, the higher the tendency to opt for short-term gain.

- Since we pay more attention to spectacular phenomena, things we categorise as small are perceived as less dangerous than big things. A mosquito is in reality more dangerous than a shark.

- Comparing available options – where one is definitely better than the other – may blind us to the fact that neither is satisfactory.

- Complexity – in the form of a high number of available options – diminishes our capacity to adequately weigh all of the options. Experts in a particular field are not immune to this.

- The default fallback option is chosen because following traditional practice takes less energy than actively breaking with it, especially when the default is given as a recommendation.

- Under omission bias, we tend to avoid actions if the future is very uncertain, and to underestimate future consequences. We prefer to do nothing even though this may turn out to be a high-risk strategy with unpleasant consequences.

- The anchoring bias describes a tendency in decision-making to over-rely on a certain reference or an incomplete picture.

- The ‹sunk cost bias› leads us to continue an unproductive course of action to try to recover losses rather than abandon it at an early stage. There is a tendency to continue a project once an initial investment is made; stopping is interpreted as recognising a mistake, a waste of resources and effort.

A selection of social biases

- Reciprocity leads to a sense of obligation to give something back to someone from whom one has received something. Criticizing donors' approaches might be perceived as an unfriendly act towards someone to whom you should be grateful.

- If we like or feel sympathetic towards someone, we may tend to agree with them or give in. We are more likely to disagree with someone we don't like.

- We place more confidence in the decisions of people with authority because we believe they have better knowledge, more experience – or more power.

- Discrimination on the basis of social identity and the stereotyped perceptions we have of people may lead to bias against certain arguments or information.

- Wanting to stick to an earlier decision can make us interpret data and argue in a particular way because we want to be perceived by others as behaving in a consistent way.

- Errors in learning from the past happen because we create a narrative around past events to fill our need to safeguard our own image or reputation, embellishing our past. This might lead to lessons learned that are based on false assumptions.

- Fundamental attribution errors explain the tendency to assume that a specific behaviour is caused by certain character traits rather than by the circumstances, while putting our own behavior down to the circumstances.

- The desire for unified voices to maintain group cohesion suppresses the motivation to acknowledge arguments that do not fit in with group thinking.

- Group polarisation describes the tendency to make more extreme decisions within in a social group than alone.

- The spiral of silence is the phenomenon that people are more likely to withhold their opinions if they feel they are in the minority, are afraid of repression or feel they may be excluded or isolated.

- Pluralistic ignorance occurs when individuals privately believe that they are the only one to hold a certain opinion, staying silent to conform to peer pressure.

Which biases can be linked to specific phases in the PA?

PA aspires to minimise an expert's bias. What is meant by that exactly? Looking at the biases listed above, it seems likely that the confirmation bias will play a prominent role. Several cognitive biases may also come into play, in addition to bias from framing, the availability bias, the complexity bias and the anchoring bias. All of the social biases may occur depending on the specific situation.

The facilitator and his/herhis/her team are supposed to substitute for the traditional expert. If aware of potential expert biases, they are assumed to take these into account and make adjustments to ensure that they do not impact on different steps in the process. For example, when setting-up the interview phase, when framing the purpose, in the selection and training of peers as well as in the data collection and analysis steps, the aforementioned cognitive biases are in the foreground. As soon as the facilitator is interacting with the peers, many of the social biases listed may play a role the facilitation teams as well as for peers.

The peer-exchange itself is necessarily framed by the ‹mandate› that is formulated for the peers regarding the intended purpose of the PA. It would be a misunderstanding of the methodology if for the sake of avoiding expert bias the process was left open without providing a clear frame for the exchange between peers, and without a clear mandate or assessment purpose. If no framework is given, the stakeholders will unconsciously frame the assessment in their own way through their interpretation of the context, the authority of the facilitator or other stakeholders, or sympathy and reciprocity – reproducing multiple biases.

The peer-exchange and its creation and collection of data may be influenced by confirmation bias, which is a consequence of sympathy and reciprocity bias. Obviously, closed (yes/no) questions are a strong indicator that the spectrum of answers is narrowed by confirmation bias.

In the data collection and analysis steps, the cognitive biases of the facilitator and his/her histeam play a strong role, depending on how the process of drawing conclusion for management decisions is set-up, and social biases also interfere significantly. There should not be a taboo around the fact that there is a dependency relationship between the contractor and the donor.

Donors, organisers and implementers should pay special attention to the interpretation of the collected data and information, and with regard to their decision-making process. E.g. confirmation bias narrows the possible sphere of learning if not dealt with consciously.

The list of biases might serve as a checklist for the different phases, to raise awareness and define specific measures in the process and to deal with the biases' impact on the results.

Further references:

Daniel Kahnemann, Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011

World Bank Group, World Development Report, Mind, Society and Behaviour, 2015Compared to an expert evaluation or an internal review, the participatory assessment attributes specific roles to various actors:

- The project funder (in most cases the organiser of the PA) is responsible for defining the scope and the purpose and for the overall design of the process, in close cooperation with the facilitator. The funder navigates the complexity of the process, with a view to tapping into the potentials and managing the risks. The funder is responsible for responding to the conclusions at the level of management, and manages the overall organisational learning processes.

- The individuals and groups targeted are not only valued as resources, they are expected to actively contribute insight about the intervention, from a more genuine perspective that is less framed by the evaluating experts or project managers.

- ‹Peers› are expected to frame the data collection (through exchange and interviews) and generate insight together with the targeted individuals and groups. Peers should be perceived by the individuals targeted by the intervention as part of their group. The assumption is that target groups are more open in expressing their views in an exchange with peers than in an exchange with experts or project stakeholders.

- A facilitator (independent from project management) takes responsibility for organising the data collection, facilitating the exchange, analysing, interpreting and documenting the results (as far as possible together with the ‹peers› and target groups).

- The project's implementer also plays a specific role. The implementing structure has established links and relations with target groups and disposes of data and information that is needed for contacting the targeted groups and peers. The implementer is an important stakeholder who can provide highly important insights and must contribute to the validation of the findings. On the other hand, the performance of the implementer is also the object of the assessment and should not be involved in the primary research activities.

Taking into account the very active role that is expected from targeted individuals and groups in the participatory assessment, this methodology might not always be the most appropriate.

For example, students who have finished a training module under the programme at stake and then moved on to other professional activities might not be interested in or motivated to invest considerable time in assessing the training programme in detail. In other cases, where target groups are more constant (e.g., farmers involved in a long-term programme), they will be much more interested in learning from the assessment for their own future, and motivated to contribute. In any case, the target groups and the peers need to understand their active role, be available and ready to contribute in a meaningful way.

Good communication and a certain level of trust among the facilitator, the target groups and the peer groups are key for making the PA empower the interlocutors and increase downward accountability of the intervention at stake.Similarly to other methods, there is no blueprint or ‹one size fits all›. Participatory assessments require particularly careful design and management of the evaluation process. This must respond to the identified purpose, taking to account the context, clarifying expectations and balancing the various dynamics that might evolve throughout the process. On the one hand, the PA's purpose and the intervention's objective and set-up must frame the scope and design of the assessment to make the synthesised results useful for the intervention's management.

On the other hand, the active role of target groups and peers is expected and welcomed as it may bring new ideas and dynamics – although there may be a risk of going beyond the original purpose, reducing the assessment's relevance for the intervention, or even of doing harm.

For example, conducting a PA in fragile and/or conflict-affected situations requires conflict sensitivity to avoid doing harm to targeted individuals and groups who might fear for their lives and livelihoods if they express critical views. They might not trust the assessment process enough to express their real views.

As for other methodologies, PA process designs depend on the characteristics of the intervention at stake – and the involved target groups.

For example, a participatory assessment of an agricultural programme directly supporting farmer groups or value chains will have to be designed differently to an assessment of a programme focusing on institutional support of the agricultural ministry.

A participatory assessment requires a certain investment, which can be managed by careful scoping and process design, keeping an attractive cost-benefit ratio. Adequate financial and human resources should be available and well-planned at every stage of the process.

The quality of the PA results depends mainly on the engagement of the donor, the programme management throughout the process, and the capacities and availabilities of the actors involved.

To sum up, the participatory assessment methodology has great potential. If done well, the PA can:

- provide key insights on how to improve the inclusiveness of an intervention by creating a more differentiated understanding of the target groups and their different perspectives on results, needs, challenges;

- make blind spots visible, reveal new dimensions by listening to real stories which contributes a different kind of data and may change our understanding of the context;

- contribute to making future interventions more effective, sustainable and responsive to the needs of target groups;

- challenge the theories of change, the logic of the intervention and the priorities set by the project/programme, subjecting them to a reality check;

- contribute to making management processes more participatory and inclusive, improving relations between project management and target groups, establishing trust and empowering and motivating them to become engaged;

- identify unexpected/ unintended effects of an intervention.

The PA process might lead to negative consequences:

- At the level of programme management: If the purpose, scope and process are not clarified carefully, the cost-benefit ratio might be inadequate, which means a lot of work was done for meagre results that are not useful for programme management. In addition, if the process is not guided and implemented with a thorough understanding of its complexity, the conclusions may be misleading and do harm to the project/programme and its beneficiaries.

- At the level of participants: If the conflict risks and power dimensions are not identified and managed properly, participants who express critical views may be exposed to negative consequences in their communities. Another risk is that the process may raise expectations that the project/programme cannot respond to.

- At the institutional level: If the process is not well designed and coordinated with the partners, a PA may do harm to the reputation of SDC and its implementing partners.

Beneficiary Assessment Report on Opportunities for Youth Employment (OYE Project), Tanzania

PDF765.27 kB1 November 2017

Beneficiary Assessment Report on 'A Systematic Understanding of Farmers' Engagement in Market System Interventions: An Exploration of Katalyst's Work in the Maize Sector in Bangladesh'

PDF1.40 MB1 June 2017

Rapport d'évaluation des impacts du projet EPA-V, projet eau potable et assainissement, Haïti

PDF1.21 MB1 June 2016

Evaluation par les Acteurs du service de l'eau, concept pour l'évaluation des impacts du projet EPA-V, Haïti

PDF827.17 kB20 March 2016

Evaluación participativa de actores del proyecto PROJOVEN, Honduras

PDF1.62 MB1 January 2016

Step by step: Conducting Beneficiary Assessment with Communities, Lesotho and Eswatini

PDF108.30 kB1 January 2015

Evaluación participativa por protagonistas del Programa Ambiental de Gestión de Riesgos de Desastres y Cambio Climático (PAGRICC), Nicaragua

PDF7.13 MB1 October 2014

Beneficiary Assessment of Improving Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Status in the Kurigram and Barguna Districts of Bangladesh

PDF807.45 kB1 March 2014

Beneficiary Assessment of Community's Perceptions on Rehabilitated and Improved Water Resources in Miyo Wereda, Borana Zone of the Oromia Region, Ethiopia

PDF1.65 MB1 December 2013

Final Summary of the Beneficiary Assessment Workshop in Panama

PDF964.84 kB1 October 2013

Beneficiary Assessment of the Water Resources Management Programme (WARM-P), Nepal

PDF1.92 MB1 September 2013

Reflections on Beneficiary Assessments of WASH Projects in Nepal and Ethiopia

PDF6.40 MB1 September 2013

Beneficiary Assessment – A Participative Approach for Impact Assessment, Central America, Bolivia and Kenya

PDF1.13 MB1 January 2013

Public Audits in Nepal

PDF715.79 kB1 November 2012

Impact Assessment of Pull-Push Technology developed and promoted by ICIPE and partners in eastern Africa

PDF2.62 MB1 March 2010

Informe Resultados Evaluación Participativa por Municipios (EPM), AGUASAN, El Salvador

PDF1.79 MB1 August 2008

Valoración Participativa de Impacto - Programa ATICA, Bolivia

PDF2.42 MB1 September 2006

Valoración Participativa de Impacto - Programa Nacional de Semillas (PNS), Bolivia

PDF2.60 MB1 December 2004

Valoración Participativa de Impacto de proyectos productivos con manejo de recursos naturales, Bolivia

PDF2.66 MB1 July 2004

Evaluación Participativa por Productores EPP, El Salvador

PDF1.57 MB1 April 2003

Informe de Resultados -Evaluación Participativa por Productores y Productoras, Honduras

PDF356.29 kB1 March 2003

Evaluación Participata por Productores (EPP), Nicaragua

PDF799.11 kB1 February 2003

Beneficiary Assessment: An Approach Described

PDF68.75 kB1 August 2002

Evaluación De Beneficiario de la COSUDE - Nota de Cómo Hacerlo

PDF463.63 kB1 May 2013

SDC How-to-Note: Beneficiary Assessment (BA)

PDF310.21 kB1 May 2013

Testing the Beneficiary Assessment methodology in the context of external project evaluation

PDF440.97 kB20 December 2012

Beneficiary Assessment: the case of SAHA (Madagascar)

PDF835.96 kB30 January 2013

Beneficiary Perspectives in the Water Consortium

PDF924.86 kB30 January 2013

Citizen engagement through Visual Participatory Processes (Bosnia & Herzegovina)

PDF474.04 kB30 January 2013

How does BA relate to results-based management at SDC?

PDF553.41 kB30 January 2013

Public Audits in Nepal

PDF715.79 kB1 November 2012

Whose Learning and Accountability? Working with citizen researchers

PDF873.57 kB31 January 2013

Participatory Assessment Step by Step

There are different ways of operationalising a participatory approach. Drawing from SDC’s and its partners’ experience, a participatory assessment can be operationalised through the seven steps described below.

There is no fixed blueprint, however. While the previous page has provided some examples illustrating different approaches, no templates are provided here as they might be misleading and not take the set purpose and context sufficiently into account. The process must be tailor-made based on the considerations that are further explained below.

Key questions to answer: What is the assessment's purpose? What will we use the results for? Is the PA the appropriate methodology in light of the programme and its specifics? Do we have the necessary (human and financial) resources? How are we framing the process?

Responsibility: The programme funder and/or implementer

Tasks/outputs:

Analyse context, logframe and programme conditions. Develop a general concept (scope, purpose, general approach and process steps, distribution of roles and tasks, risks to be aware of, timeline). Make human and financial resources available, budgeting the process. Recruit a facilitator who will be mainly responsible for the specific process design, managing the data collection and analysing the results. Organise and conduct a scoping workshop with key partners and a resource person that is familiar with the PA methodology (if needed), to confirm and fine-tune the purpose, build a common understanding of the conceptual approach and the process.

Possible purposes:

What are possible purposes for a participatory assessment? Some examples:

- Getting a systemic understanding of the factors that shape the target groups' choices.

- Finding out whether the prodoc's assumptions and the theory of change reflect the realities that the target groups are living in. For example, verifying the ToC ‹Better education leads to sustainable integration of the targeted individuals in the economic development of the region›, or ‹increasing the competitiveness of farmers and small enterprises by facilitating changes in services, inputs and product markets will lead to increased income for poor men and women in rural areas.›

- Understanding the needs and aspirations of target groups with a view to tailoring the objectives of an intervention.

- Understanding the various levels of effects and results that the intervention might have had, or its contribution to change in the lives of target groups. This could focus on various areas linked to the logframe and beyond (e.g. safety and security, gender equality, access to basic services, etc.).

- Understanding the homogeneity or heterogeneity of target groups, with regard to a planned intervention.

- Assessing the appropriateness of the monitoring system (indicators, sources of information, methodologies) and project approaches.

Criteria which make a PA particularly appropriate (e.g. long term relation with target group)

A PA is particularly appropriate if and when:

- It is assumed that the voice of beneficiaries for whom the programme is designed has not been heard clearly or loudly enough. By listening to the target groups, views, values and beliefs, it can be expected that the specific socio-cultural dimension of the intervention will be improved.

- Other monitoring and evaluation approaches focused on quantitative rather than qualitative indicators.

- There is a strong interest in learning about the target groups, about their diversity and how it is mirrored in the programme, and in deepening the understanding of the context through a broadening of perspectives.

- A genuine interest in challenging the programme's assumption of how the systemic interactions between the programme and the context can be described. A programme manager summed up the concept of ToC brilliantly: “With all the knowledge I have about the context, the ToC is what I would have been betting on to be effective."

- The programme is conducted in various regions representing different contexts, e.g. more or less exposed to violence or conflict. A comparison of the respective ToC and theories of action (ToA) allows for more specific adaptation of the programme. A long-term relationship with the target groups makes it worth investing in empowerment and ownership through participation.

- Ongoing cooperation between, organisers, implementer and the stakeholders of the programme make it worth investing in building and strengthening relationships and organisational learning.

- The programme is expected to improve on responsiveness, to make it more demand led and poverty oriented and clarify the accountability of different stakeholders to the target groups.

Examples for the objectives of a scoping workshop

Example for the objectives and expected results of a scoping workshop.

The design and length of the workshop depends on the invited participants and their expectations, the number of participants and the possible preparatory steps preceding the workshop. In some cases the ‹national facilitator› has been selected before the scoping workshop to allow for a more in-depth reflection on the adaptations to the methodology.

Objectives of the workshop:

Clarity among all involved stakeholders on the PA as an assessment and the necessary planning and decision making in relation with the PA

Expected results of the workshop:

- The PA methodology is understood and the adaptations for the PA for the specific programme are clear

- Methodology selected

- Scope, purpose and framework of the PA established

- Understanding established of the framing and set-up of the PA

- Different PA options developed

- Concrete planning steps for the PA established

- Selection criteria established for national facilitator

Key questions: How do we design the process in detail? What target groups will be involved? Which peers will facilitate and accompany the data collection in the field, and how? Who will support the facilitator in their tasks? What profiles and capacities are required in the facilitator's team? Which target groups and individuals to include? How do we recruit them and gather their viewpoints?

Responsibility: Organisers and facilitator

Tasks/outputs:

- Recruit the facilitator's team.

- Fine-tune the roles of the process actors, methodology for data collection, documentation, analysis and validation, in the light of the purpose: who, when, where, what, how.

- Plan for feed-back loops for managing risks, learning and steering throughout the process.

- Define criteria for selecting and identifying interlocutors, recruiting peer assessors.

- Develop practical tools (communication with and messaging for stakeholders, target groups and peers, instructions for facilitators, interview guides, questionnaires, reporting formats, monitoring tools to monitor the assessment process).

Things to consider when identifying interlocutors

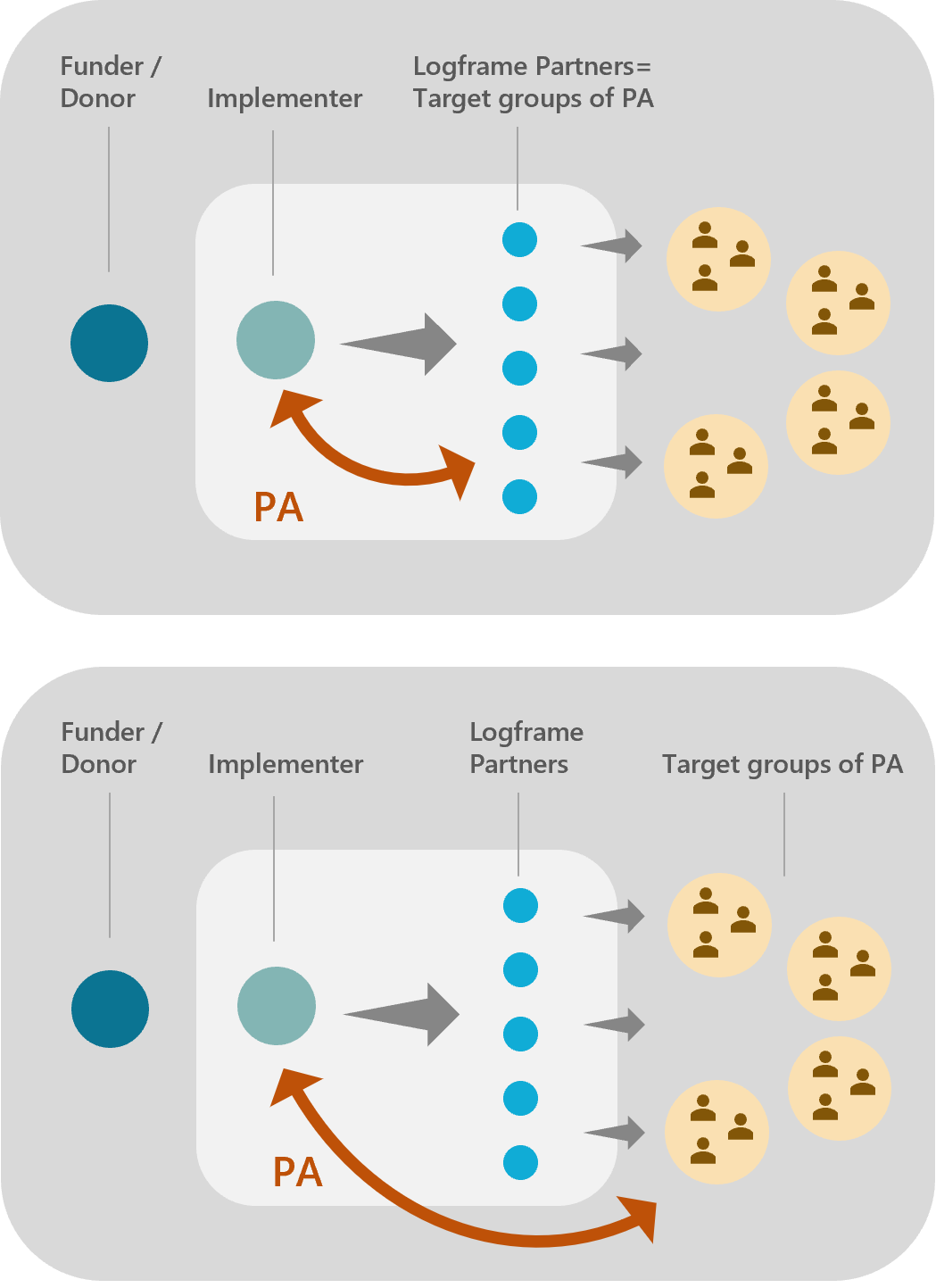

- Interventions target different stakeholders and groups. The SDC’s programmes and projects often support partner institutions that are expected to have an impact on the lives of individuals (‘end beneficiaries’). Thus, the logframe expects outputs and outcomes mainly at the level of the targeted institutions – with some general expectations at the level of impact on citizens. If and when the funder directly involves ‹end beneficiaries› as target groups in a participatory assessment, it may be going beyond the direct targets of the logframe system – and that comes with some challenges: who is learning what from the assessment? Are we empowering our intervention partners or a group of citizens (the target groups of our assessment) by giving them the power to assess the performance of our partners? Are we really assessing the impact that might be attributed to the intervention? How much is the reality that is assessed by the end beneficiaries linked to our intervention at all?

- Working with institutions as target groups comes with specific challenges in terms of participatory assessments: Who represents the institution? Who is considered a ‹peer›? Who would be acceptable and independent enough as a ‹peer› interlocutor? What is the relationship between the two? How do you distinguish between the opinion of the individual representatives and the organisational viewpoint? How do the opinions depend on political power relations and interest? How sustainable is the qualitative data from the interviews? E.g. will it change after elections? All these questions merit in-depth political analysis and a systemic understanding of the institutional set-up.

- Examples for terms of reference of the facilitator and co-facilitator (link to examples for ToRs)

Key questions: What will be the concrete role of ‹peers›? How do we build a common understanding with selected target groups and peers, with a wider circle of stakeholders? How do we assess and build the competences of peer assessors? What are the topics and questions for the exchange between targeted individuals and peers? How do we document their insights? Does the approach work in practice?

Responsibility: Facilitator, together with organisers

Tasks/outputs

- Frame, organise and programme the collection of data (inviting target groups and peers, deciding on methods and approaches to use, logistics, reporting).

- Prepare and share information with local stakeholders.

- Hold capacity-building workshop with peer interviewers, develop and adapt key questions to their needs and perspectives.

- Test and refine the approach in a pilot with selected target groups and peers, validating data collection approaches and questionnaires and re-formulating messages and questions if needed.

- Fine-tune and validate the approach after piloting, together with organisers.

Additional recommendations and resources

- Data collection may be organised in a great variety of forms and formats, from individual interviews to focus group discussions, in presence, by phone calls or virtual means. The selection of the adequate methodology needs careful reflection and taking into account the context, particularly the conflict and power dimensions.

- The way a facilitator interacts and communicates with the local stakeholders will differ from the way the implementing partner is used to work, due to their different roles. Therefore, it is important that the facilitator and the implementing organisation have clearly defined roles and are able to cooperate well in order to organise the field visits efficiently and effectively.

- The collaboration can only be successful if there is a mutual comprehension that the assessment serves organisational learning of the funder and the implementer. The intention of the PA is not to discover the ‹errors› of the implementer but to bring new insights to the process. At the same time there is a certain dependence (and power relation) between the implementer and the donor that should not be taboo. This is challenging if the PA is preparing for a next phase that will be tendered out. While the implementer should be part of the learning process, according to the rules on public tendering, they should not be especially involved.

- The field visits need thorough planning, anticipation of problems, a follow-up in the field, and flexibility, taking into account conflict risks and power relations between partner institutions and individual beneficiaries. All adaptations to a specific context should be documented, to enhance the transparency of the process and make it easier to interpret data.

- Different axes of empowerment for peers:

© Miseli, Fabrice Escot Key questions: Are the target groups' views being collected and documented as planned? What do peers need in terms of support? What are the upcoming challenges and risks, and how will you deal with them?

Responsibility: Facilitator and his/her team, with the support of the organisers

Tasks/outputs:

- Inform identified target groups and other stakeholders about the expected process, methodology and results.

- Train peers in their pre-established role and methodology.

- Organise meeting places and logistics.

- Create regular space for frequent reflection on the process (with peers, among facilitators, with organisers).

- Facilitate and support data collection and reporting.

A regular, even daily exchange among facilitators and peer interviewers (possibly with organisers) is needed to adapt the approach and data collection programme to the evolving context, upcoming needs and risks. This has proven to help the facilitator develop a more thorough understanding of the process and its results.

Additional recommendations and resources

Different views should be reflected as fairly as possible in all aspects of the PA process: design, data generation, analysis and communication of findings and recommendations, bearing in mind possible risks for different groups. Possible bias of participants, distortion or lack of ownership should be reflected on and documented, explicitly explaining the extent to which it was possible to meet PA principles in the report or documentation. With the purpose of better contextualising the collected data, a ‹mini-questionnaire› for the peers asking about certain aspects of their socio-economic context may prove helpful. Finding out about the rationale of the peers when selecting and phrasing their questions to the interlocutors may create more clarity for the subsequent interpretation.

Key questions: How to analyse the raw information and synthesise the findings from collected data? Which biases might have influenced the data collection, and which biases could influence the data analysis? What are the key results to communicate? How to validate the findings from the perspective of target groups and peers and from the perspective of programme management and funders? What to conclude from the findings?

Responsibility: Facilitator and his/her team

Tasks/outputs:

- Collect the reports from data collection.

- Triangulate the data, analyse and synthesise the findings, draw conclusions in relation to the purpose of the assessment and take into account the possible influence of context factors on the data (such as violent conflicts in the community, or power relations between different target groups).

- Discuss and validate the findings with interlocutors, peers and/or experts, partners, management, funders.

- Refine the synthesis and conclusions.

Key questions: What form of documentation and reporting of results is most useful in light of the purpose of the assessment? How did the planned process work out? Was the selection of interlocutors from target groups and peers appropriate? What were the challenges faced by the facilitators? What factors have been considered when interpreting the results? What is the information to share and communicate as a result, and with whom?

Responsibility: Facilitator

Tasks/outputs:

- Documenting the collected and validated data, analysing the process and (self-critically) identifying the challenges that could influence the results.

- Producing a synthesis report in line with the purpose of the assessment, with interpreted results and conclusions in light of the challenges.

- Sharing and discussing results with organisers, project management, programme partners, according to the set communication strategy.

Additional recommendations and resources

Important considerations for synthesis report

Synthesizing results needs to be based on and framed by the purpose of the assessment and the assessment questions. The process will produce a series of stories told by target groups and peers, from a variety of perspectives and in different forms and terminology. The results must be summarised from the perspective of the facilitator, contextualised (related to the context of the target groups and that of the assessment process), and then analysed, with a view to providing conclusions and recommendations for the organiser. The authors will inevitably incorporate their perspectives (incl. biases). The analytical framework and biases should be made visible as far as possible.

Beyond the conclusions and recommendations for the management, the synthesis report should contain information about the assessment process and the impact of the specific process design (effects of empowerment, individual and institutional learning, change of relationships) – and reflections on the assessment process itself.

Key questions: What does the organiser's institution take from the assessment results? Do the results question our theories of change? Theories of action? Strategic orientation? Partners, approaches and methods? How will the intervention be adapted? Where is there inter-institutional learning – between funder, implementer and partners? Personal learning by staff? Who should learn and understand what? Who is motivated to learn? How can you focus the effort of learning and communicating beyond the operational adaptation of programmes? How can interlocutors (target groups and peers) be informed about the results, so that they can see that the management responds to their views and their contribution has been taken seriously?

Responsibility: Organisers (funders and programme implementers)

Tasks/outputs:

- Understand, integrate and interpret results in the light of the purpose and the process.

- Take and implement management decisions (management responses).

- Communicate decisions.

- Document learning, capitalise on and share experience from the process, in written or multimedia formats.

- Share results with interlocutors (target groups, peers, stakeholders) about the results and the management responses taken.

Additional recommendations and resources

- The design of the learning process needs to reflect the key question: Who is learning what to which purpose? It will take different steps to gather learnings from individual stakeholders and transfer individual learnings to a collective and an organisational level.

What to consider when planning and implementing a participatory assessment

Participatory assessment implies more than organising peer interviews – it is an assessment methodology that involves target groups and peers actively in producing and collecting data.

In the comprehensive and coherent design of the assessment process lies the power to produce useful and focused results. Thus, a successful participatory assessment depends on a variety of issues.

10 questions to consider

The participatory assessment makes sense when the SDC or its implementation partners want to acquire food for thought and are ready to invest their own time and resources to validate the conclusions and deeply reflect on the results and its consequences. The participatory assessment is particularly useful for planning a new phase of an already established intervention. If the organisers have little flexibility to take up new ideas and adapt their approaches, the participatory assessment methodology may be too resource intensive.

The participatory assessment is adequate, if and when:

- There is a perceived need for getting out of the box of current thinking around the intervention.

- The assessment has a clear forward-looking learning purpose, to find out how best to design and implement a future intervention or a next phase of a project.

- The context is appropriate for target groups and peers openly expressing and discussing their views.

- Target groups and peers would see an interest and intrinsic motivation in contributing to the assessment pro cess.

- The organisers have the necessary commitment and the required financial resources, human resources and logistics are available.

- The assessment process can be expected not to do harm to the target groups or their peers ('do no harm' principles).

The organisers (SDC office or implementers who are mandating the PA) are responsible for setting out a coherent and adequate framework for the assessment process, designing, steering and accompanying the process and implementing its result s. The preliminary considerations are the purpose, objectives and scope of the assessment. What do we want to find out through this assessment? Do we want to check whether our theories of change are adequate and relevant to the realities of targeted groups? Or do we rather want to find out whether and to what extent a certain methodology or training topic responds to the needs of targeted individuals and groups?

The framing and design of the assessment process should be carefully considered, with external support for the organisers when needed. If the purpose of the assessment is not clear (enough) the PA carries the risk of being very resource intensive and producing few useful results.

Main tasks of the organisers:

- Set the scope and focus. Define the purpose of the exercise, based on a clear view of the intervention, the partners and the institutions involved: For what and how will we use the results of the assessment? What are the questions that need to be answered?

- Recruit a facilitator for the process, ensuring that he/she has the required human and financial resources.

- Accompany the process, steer it towards its purpose at all stages; make sure that the conflict dynamics are dealt with and the ‹do no harm› principles are followed.

- Provide space for reflection and feedback loops to adapt the process if the conditions prove to be different than expected.

- Provide space for individual and institutional learning, clarify who should be informed about and learn what, when, how, and for what purpose.

- Make sure that stakeholders, target groups and peers are informed adequately about the process and its results.

- Plan for integrating the assessment's results into its own decision-making on future interventions (in terms of ToCs, project approaches, project design, partnerships, risk assessments).

Main tasks of the facilitator (in cooperation with the project management)

- Designs the PA process steps and defines the adequate methodology in detail, respecting context-specific challenges e.g. conflict sensitivity.

- Recruits team of co-facilitators (if needed), with the required profile.

- Sets out the work programme.

- Selects targeted individuals and peers to be involved in data collection.

- Designs and organises the appropriate methodology for data collection ('peer interview process').

- Steers, manages, organises and monitors the process of data collection.

Key competences of a national facilitator

To fulfil complex tasks, the facilitator must have a strong professional and personal profile.

The facilitators should understand the participatory assessment approach and qualitative assessment methodologies, and have professional experience in this respect. He/she should know the intervention's context, have competences in designing and facilitating participatory learning processes, strong communication skills, be able to interact with people from different backgrounds and status, identify and deal with different types of biases, and be able to identify and manage conflict and power relations.

The attitude of a curious researcher rather than an evaluator should guide all interventions of the national facilitator. He/she needs to work with a genuine appreciation of and trust in the competences of the peers.

Finally, analytical and synthesizing capacities are needed to produce, from a wealth of data, a concise report for the organisers, as a basis for their management decisions.

Specific attention must be paid to the scoping, design and planning. Experience shows that a scoping workshop is useful for developing a common understanding of the purpose, identifying the expectations from the assessment, focusing on relevant questions, establishing the cornerstones of a process that is fit for purpose, taking to account the risks involved. It also helps identify the required resources and the financial costs to budget for the assessment – and to make an estimation of the cost-benefit relationship. A careful scoping and clear thematic focus considerably help reduce the investment.

Careful conflict and power analysis regarding the intervention and assessment process is needed. The PA itself may involve specific risks, for the participating individuals as well as for the assessed intervention. If the process is not designed and managed in a conflict-sensitive way and discrimination issues are not treated properly, the PA process may even do harm. For example, it may expose targeted individuals and groups or peers to reprisals. Or the results of the participatory assessment may only reflect the views of individuals that have vested personal interests and are far from representing the target groups. Since many actors need to be coordinated in a PA, a written documentation of key information and findings reflects good organisational practice.

Feedback loops between the organisers and the facilitator and his/her team must be established throughout the process, and the planning should be adapted flexibly to emerging risks and potential benefits.

Target groups are not homogenous. Some groups and individuals will have benefitted more than others from an assessed intervention due to power relations and other factors – and they all might express very different views on the results of a particular intervention. A key challenge is selecting individuals who can represent the target groups that the intervention was planned to be responsive to, taking into account the diversity while keeping sight of practicability and costs.

Participatory assessment is a qualitative approach. A certain quantity and diversity of views will be needed to ensure a certain representativeness of the collected information. For example, to get gender disaggregated data, both men and women from target groups will need to be involved. However, larger samples do not add quality per se. The rigour of the results stems from the careful and well thought-out selection and design of interviews and not from numbers in samples. E.g. involving more school teachers with the same contextual background might not add new qualitative insights, and just create more costs.

In general, interlocutors should be selected based on their proximity to the project goals and activities, their knowledge and experience on the topic, and their motivation to contribute.

Whom to select?

The criteria will depend on the purpose of the assessment, the questions to answer, the intervention at stake and the context. For example:

- Do we want to compare the impact of different learning methods? Then we might focus on teachers and students who were involved in the different approaches, and we might add a group of students that were not involved in the project at all.

- Do we want to assess the usefulness of the learning content? Then we might focus on former students who are in a position to express their opinion on its practical usefulness.

- Do we want to know more about the performance of teachers? Then we might select current and former students and their parents.

Motivation of target groups by personal interest in the results, for example:

- If target groups have been constantly and continuously engaging with the programme (e.g. farmers in a local agriculture programme), they may have a strong motivation and interest in contributing to the learning and improving the intervention they will continue to benefit from.

- In other cases, there might not be a strong genuine interest among target groups to contribute to the PA exercise. For example, if students are not aware of the fact that they are benefitting from a project intervention, or if they benefitted from one activity or phase of an educational programme but have since moved on. In this case it might be difficult to motivate them to contribute if no additional mutual benefits are identified.

The selected peers share important characteristics with the target groups but should be outside the intervention's direct reach and impact. It is assumed that familiarity with the context and similarities between peers establishes trust, so that target groups will buy into exchange with them and openly share their views and opinions – more openly and genuinely than with external stakeholders or experts.

However, people may be ‹similar› with regard to one aspect – and very different in other respects. Organisers and facilitators may consider in their subjective external view two individuals or groups as peers while the individuals concerned may not consider themselves peers at all (see «Similarity» below).

Peers should be recruited according to clear criteria of ‹similarity›, taking to account their capabilities, their own motivations and interests in the intervention and/or the assessment, and their relationship with the beneficiaries. In recruiting peers, it is important to consider what could motivate them to invest their time in such an exchange and contribute to the assessment process. It may be difficult to establish any intrinsic motivation.

Peers are assumed to play a neutral and impartial role of data collector for the organisers. This might not be well understood either by the peers themselves or by the involved target groups. Some peers might not stick to the set of interview questions and may take on a more investigative role, so that peers can be perceived as intruding or even spying into the lives of interviewees, which could entail personal risk for all involved, particularly in conflict-affected situations. Target groups and peers both live in a reality of complex interactions and relationships (including with the intervention's implementing partners).

Peers and target groups might have specific motivations to be involved in the assessment – be it only the concern of satisfying the donor to continue the support. While this can't be avoided per se, it is the facilitators' role to build a shared understanding, instruct the peers on their role, provide adequate information to the target groups, monitor the data collection process and detect the factors that risk hampering the peers' neutrality and the authenticity of the expressed views. It will also be his /her task to take such factors to account when analysing and synthesizing the data collected from peers.

Facilitators will need to find ways to bring forward and strengthen the knowledge and capacity of the peers to make their interlocutors express their views, document and collect data according to the design of the assessment. They will need specific information, training (including interview techniques) and coaching to help them understand und fulfil their particular role and the important tasks in the process. A specific challenge is to engage with institutions in a participatory way (see key questions in 'step 2').

‹Similarity›: What decisive features to potential peers have in common?

It is always challenging to define ‹similarity›. For example, is it the belonging to a similar territorial community? Similar living conditions? A neighbouring village? A similar social or educational status? The same beliefs or shared values? Similar development challenges? The same gender? The criteria for ‹similarity› must be considered carefully in the light of the intervention and the context at stake, and the aim of establishing a basis for trust between the interview partners.

Relationships among target groups and peers must be examined carefully, not only when selecting the peers but throughout the process of exchange. In the light of complex power relations within societies, trust and confidence is never to be taken for granted and must often be built or strengthened, particularly in fragile and conflict-affected situations. Possible security risks for the facilitators, target groups and peers and their individual fears must be dealt with throughout the assessment process and are particularly important for framing questions, selecting the interlocutors and organising the logistics.

The exchange between selected target groups and peers is framed by the context of the programme and the objectives of the PA. The challenge for the organisers and the facilitator is to keep this framing but not distort the data and unduly influence the exchange. They must be careful in their communication and explanations of the exercise. It might seem that communicating as little as possible around the purpose of the assessment might reduce expert bias, however that is not the case. If peers and target groups are not clear about the objectives of the exercise, they will find their own explanations and (mis-)interpretations – and might fulfil a wrongly perceived role, most of the time with the best intentions. In such cases, the collected data will present strong biases and be difficult to interpret (link to level 3.1 Bias).Participatory assessment is not only about bilateral interviewing. Depending on the purpose and the context, the exchange between target groups and their peers can take place in different formats according to the purpose, context and available resources. For example, facilitated group discussions may simplify the approach and make it lighter while providing differentiated views of stakeholder groups. Remote interviews, phone calls or video calls can also be considered.

The questions for the interviews and/or discussions as well as the interview methodology should be identified and formulated in close cooperation between the facilitator and the peers, with a view to incorporating the realities of the target groups and collecting relevant data to answer the general questions of the assessment, but also to allow for new and unexpected insights. (link to level 3.2 examples for phrasing the purpose)

In many cases, the task at hand will need to be expressed using concepts, terminology and a common language shared by peers and target groups. A story-telling methodology, the use of pictures, photos, metaphors, anecdotes (and other creative methods) may help produce useful data for analysis, even in contexts where written reports will be challenging. (link to 3.3 Facilitation)Also decisive for building trust are a precise, reliable location for the meetings and confidentiality rules. (link to level 3.4 The environment of meetings)

Peers must receive basic training to develop trust in the process and acquire a common understanding of the main features of solid data collection. These include a ‹neutral›, impartial, empathetic perspective; a common format, with clear interview questions for accurate data collection and reporting; basic interviewing and reporting skills. For example, it is important to make sure that peers know the difference between closed (yes/no) questions and open questions (that allow for a more extensive/flexible response).In general, organisers, facilitators, target groups and peers must be aware of their different roles in the exchange, and the expectations of all stakeholders must be managed. Good messaging and communication are key, also towards other stakeholders in the intervention (e.g. local authorities, implementing partners).

Bias Management

See «Bias Management» above

Example for phrasing the purpose:

The assessment questions are part of the ToR of the facilitator. The interview questions are a separate set of questions which are framed by the purpose of the assessment and the assessment questions. It is the task of the facilitator to explain the purpose and the assessment questions to the interlocutors of the peer interviews, who then develop their own interview questions. As an example, in the case of vocational training, different assessment questions are possible. Their phrasing will determine the direction and the space for discussion and interviews. The seemingly subtle differences have a large impact on the peers’ understanding of the task. This phrasing is thus of key importance for the PA. Examples for the different framing of the purpose of the PA in the introductory communication of the facilitator with the peers are: «We want to find out what your interlocutors think might be a good education.» This leads to a narrow approach focusing in the interviews on views of «good» and «bad» education. «We want to find out what the strengths and weaknesses are of the training methodology used.» This implies that peers and target groups are able to compare different methodologies and are aware or even specialists on adult learning. «We want to find out what your interlocutors think this education programme has achieved? What did they learn from it?» This leads to linear causal thinking on the results of an intervention – not taking to account the systemic dimension. «We want to find out how and why the life of your interlocutors has changed since the training events.» This opens the discussion to a broader awareness of systemic interactions of different factors and gives an opportunity to challenge the underlying theories of change of the intervention. From this introduction as to the purpose, the peers will develop their interview questions. The PA process must allow space for additional questions from peers and interviewees. While the format and content of interview questions will differ depending on the context and the interlocutors, a certain rigour in following an interview guide and uniform formatting of the questions for discussion will help make a sound analysis and to synthesise the answers. Special attention will be needed to translate the questions from the ‹development jargon› into everyday language and from the project’s working language into local languages. It may impact strongly on the results and on the process itself if the interviews are not conducted in the mother tongue of either peer or interviewee, or facilitator.Facilitation

An adequate interview methodology is key for getting good results worthy of the considerable investment. The facilitator's team must possess strong communication skills.

It is primordial to construct a safe space for the exchange. Security requires an atmosphere of trust, not just physical safety. The facilitators must pay attention to group dynamics, the inclusion of extra- and introverted individuals, culturally acceptable ways of expressing criticism, the importance of saving face, the presence of other people (e.g. authorities of any kind) in the room etc.

It may be necessary to work with alternative methods of data collection such as story-telling, or to link different exchange formats, such as exchanges in small groups and exchanges in peer/interviewee settings, in order to adapt the methodology to the context.

Conducting interviews by phone has the advantage that you can reach out to stakeholders who are relatively inaccessible, e.g. due to the security situation. This can be part of a remote management set-up.The environment of the meetings frames the results. Example from experience